It was the most priceless artifact in ancient China—then it disappeared

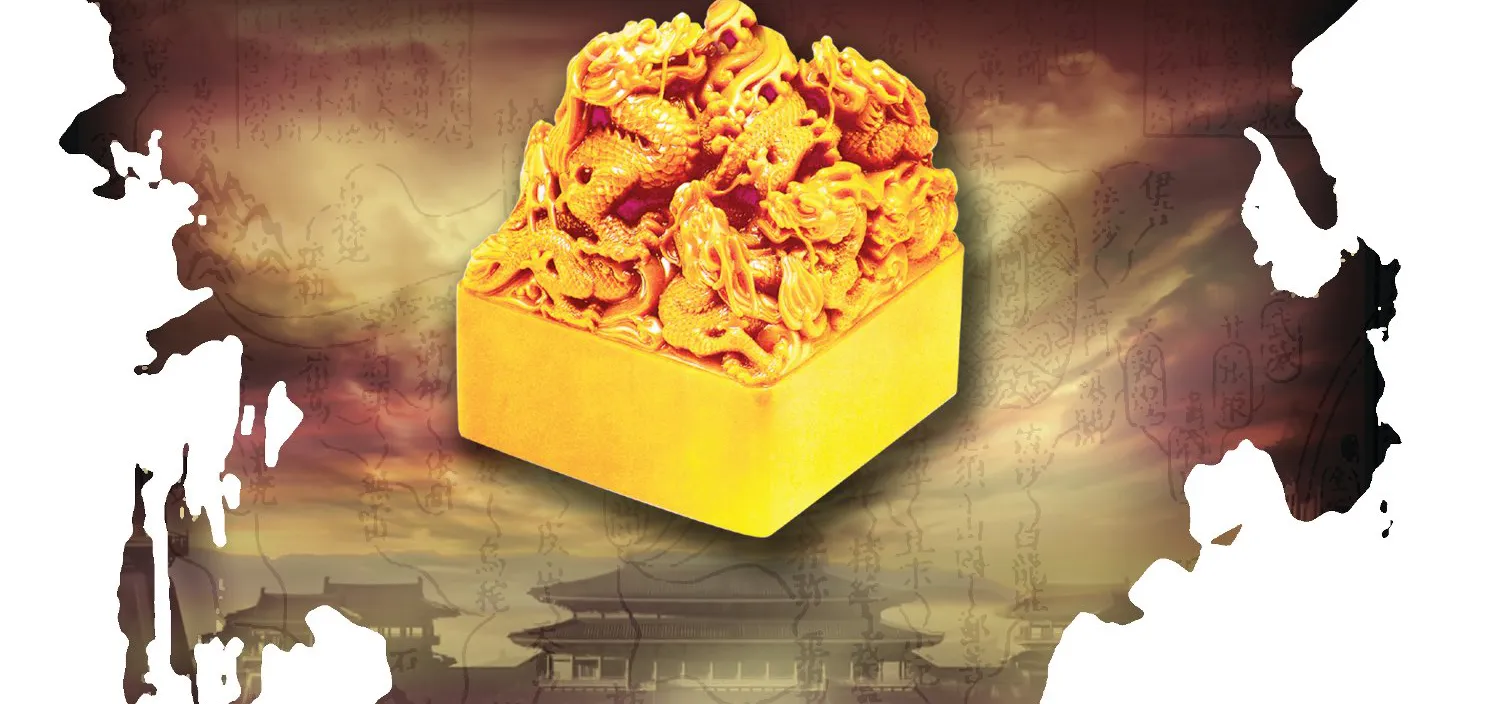

If the Mandate of Heaven had a physical form, it would be a four-inch square block of the purest jade in the realm. Its base would be carved with dragons circling the message, “Having Received the Mandate of Heaven, Live Long and Prosper,” in case of confusion. It would have been commissioned by China’s first emperor Qinshihuang (秦始皇), and passed from ruling dynasty to dynasty—until disappearing for good over 1,000 years ago.

Sounds like the stuff of legend? The existence of the Heirloom Seal of the Realm (传国玉玺, “Jade Seal Passed Through the Realm”), as this relic was known, is well attested in ancient history books, but the object has been reported lost then miraculously recovered so frequently in its 1,000-year history that one has to take the details with a grain of salt. On the other hand, records of emperors gaining and losing what was effectively the physical embodiment of their right to rule has proven to be a useful narrative device for historians to ruminate on the nature of power.

Personal seals have been used to authenticate documents in China since at least the Zhou (1046 BCE – 256 BCE), when the character 玺 (xǐ) first appeared in the records, later becoming the exclusive character for imperial seals. Highly ornamental, usually made from jade or gold, and topped with three-dimensional carvings of auspicious symbols, the xi seems to have been used for ceremony as much as (if not more than) stamping documents. The Qing emperor Qianlong (乾隆) had as many as 1,800 seals made, but we only have records of about 30; most were crafted to commemorate events like imperial birthdays and military victories, and kept in a special hall of the Forbidden City. One of Qianlong’s seals, made of steatite and decorated with nine dragons, fetched 22 million USD at a Paris auction last December.

Likewise, no prints by the Heirloom Seal exist, and most historical paintings simply show it held in the triumphant hands of a new emperor. But it’s no great stretch that a traditional Chinese implement for personal identification could be reimagined as a stamp of identity of the realm itself. Historical records about the making of the Heirloom Seal—written in the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), the Qin’s successors—conflated the seal with the legend of the Heshibi (和氏璧), a priceless jade disk coveted by various kings during the Warring States period (475 BCE – 221 BCE). Qinshihuang is said to have turned the disk into the seal when he united the realm, and the third Qin emperor handed it to the Han’s founder as part of his surrender, thereby kicking off a new, continuous, and linear paradigm of power transfer in the history of China.

The seal disappeared multiple times as it passed down the ruling lineage. Qinshihuang, never a favorite with the Han historians, was said to have cast the seal into Dongting Lake to ensure a smooth passage for his boat; it was found and returned by an honest farmer eight years later. In periods between dynasties, rival warlords often claimed to possess the seal when they were gaining the upper hand, while it disappeared again in times when the winner was unclear. Though some records state it was lost for good when the last emperor of the Later Tang state (923 – 936) burned down his palace as the invaders closed in, records of the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127) state that it resurfaced 150 years later via another sharp-eyed farmer—just when the realm was feeling pressure from invaders in the north.

But though the seal symbolized the emperor’s suitability to rule, historians have been careful to note that it wasn’t just by grabbing the object that emperors secured a ruling mandate for themselves. When a coup was staged in eight CE by a Han official named Wang Mang (王莽), the Heirloom Seal was one of the first things he demanded from the deposed emperor’s family, and it was promptly removed from him when the Han was restored just 15 years later. The warlord Yuan Shu (袁术), according to The Records of the Three Kingdoms, advertised his possession of the seal at the same time he declared himself emperor, but other warlords rallied against him anyway because he was a backstabbing tyrant.

By contrast, Yuan’s rival, the Machiavellian Cao Cao (曹操), also claimed to have obtained the seal sometime after Yuan’s death. The Records state Cao was asked whether he would declare himself emperor, but he replied, “If heaven wills it, then I could be King Wen of Zhou dynasty.” This referenced the father of the founder of the Zhou dynasty, who never took the throne but was posthumously named as king by his son. Accordingly, Cao spent his warlord career stating that he was “supporting” the fading Han emperor, and his son Cao Pi (曹丕), founder of the Wei kingdom (220 – 265), made a show of refusing the Han emperor’s abdication three times, before agreeing with the remark, “I finally understand what it was like when [legendary kings] Shun and Yu sagely accepted an abdication.”

It seemed that the seal, like the Mandate of Heaven, was believed to act of its own accord: You didn’t seek it out, instead heaven vouchsafed it if you showed potential to govern well. In that sense it might have been quite easy for people to accept that the seal could almost magically disappear and reappear depending on how stable or centralized the emperor’s power appeared to be at a particular time.

But this was subverted by the seal’s final disappearance, which different records put at various times between the Later Tang and the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368). By the time of the Ming (1368 – 1644), the seal was indisputably gone forever—records state that the founding Ming emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋), searched as far as the Mongols’ homeland in the North, but couldn’t find the seal. The Ming era was also when emperors began to produce more commonplace, personal seals en masse, culminating in Qianlong’s vast collection; as Zhu Yuanzhang himself said, his reign was a time for the common people to “dispense with cults and fall in with the right ways.” The narrative of a mythical seal, derived from the old-school Confucian ethos of divinely mandated rights and responsibilities, may have become less significant as Zhu consolidated the realm on more secular lines—military, commerce, and stringent laws.

In recent decades, several seals unearthed in the Chinese countryside—including one by a 13-year-old boy in Shaanxi in 1955—were thought to be candidates for the lost treasure, but ended up being the many other imperial seals from the Qing and Ming. In 2015, a new conspiracy theory was reported by ifeng.com that the seal actually survived into the Republic of China and had sunk in a shipwreck on the Bohai Sea in 1948, when the Nationalist government tried to evacuate it before the Communists took Beijing.

And though this claim is supported by neither historical evidence or logic—for why would the Nationalists or anyone keep the seal a secret for so long?—ancient chroniclers would have been proud of how well this solution narratively mirrors the political limbo between the two parties at the war’s end. No farmer or fisherman has yet come forward with the find.

The Missing Seal is a story from our issue, “Wheel Life China.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.