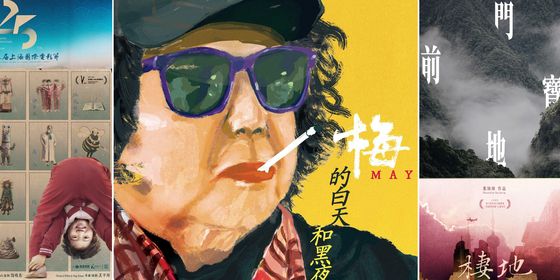

Acclaimed for its focus on cyber bullying and online rumors, the film “Post Truth” courts controversy for its shallow view on the surging social issue

Han Lu, a white-collar worker who grew up as an orphan but died in her early 30s and now lies in her grave in a cemetry, is facing an eviction order. The generous 1.36 million yuan donation she made before her death to a local child welfare institute, which made news headlines, somehow lead to the rumor that she was an escort who made the money from sexual services. Now, the children’s welfare center does not know what to do with Han’s donation, fearing it is “dirty money,” while a developer of the graveyard whose brother is buried next to Han believes she brings bad feng shui, and demands her out.

Meanwhile, cemetry agent Wei Ping’an neither believes the gossip, nor agrees to relocate Han, holding himself responsible for her as the one who sold her the plot when she was alive. To defend Han’s name and tomb, he embarks on a journey to trace the root of the rumor, online and offline, from the small city of Ji’an in northeast China’s Jilin province to Inner Mongolia over 1,000 kilometers away, only to find himself the subject of new slander.

Thus goes the story of Post Truth, the most popular movie in Chinese cinemas this March, often considered an off-season for the box office following the busy Spring Festival holiday. Directed by and starring Dong Chengpeng (also known as Da Peng), this comedy film has sold over 8.33 million tickets, and earned over 352 million yuan in revenue by March 19, nine days after its official release. On China’s most popular film review platform Douban, it was rated 7.9 out of 10, surpassing 94 percent of movies in this category on the platform, including Dong’s previous work Jian Bing Man (2015, rated 5.8) and City of Rock (2017, rated 6.6).

In addition to improved storytelling, the popularity of Post Truth is largely attributed to its depiction of cyber bullying and online sexual rumors against women, an issue that has gained increasing attention alongside relevant cases and tragedies over the last decade or so. However, the movie is also criticized for the lighthearted and shallow treatment of the issue.

In a 2020 incident that directly inspired the film (as the director has mentioned in many interviews), a Hangzhou resident known as Ms. Wu fell victim to defamation, as rumormongers used a video clip of her retrieving a package to fabricate a story of her being a married woman seducing a deliveryman. In a more recent tragedy, a young woman named Zheng Linghua took her own life this January, after dealing with nasty online comments on a photo of her showing a graduate school admission letter to her bedridden grandfather—netizens called Zheng an escort because of her pink hair, claimed she “exploited her hospitalized grandfather for attention,” and even made lewd speculations on her relationship with her grandfather. Meanwhile, a student was dismissed from Suzhou University in Jiangsu province on March 19 for posting photoshopped images of his female friends and classmates with fake accounts of their sex lives on a pornographic forum.

Can a Comedy Film Combat Online Defamation? is a story from our issue, “After the Factory.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.