Once the nation’s most popular instrument, the accordion accompanied many of China’s revolutionary moments

In 1966, the Tianjin People’s Fine Arts Publishing House issued 80,000 propaganda posters to mark the start of the Cultural Revolution. Titled perhaps prematurely, “Long Live the Victory of Chairman Mao’s Revolutionary Line of Literature and Art,” they showed a young accordionist playing a (presumably) jaunty tune, before a mob of Red Guards brandishing red books and shovels over a cowering counterrevolutionary on the ground. Above and behind them, a portrait of Chairman Mao watches benignly.

This was undoubtedly the high point of the accordion’s popularity in China, says accordion merchant and repairman Dai Guangyao, 50 years later. Once employed by the state-run Shanghai Accordion Factory, now defunct, Dai has experienced the rise and fall of the shoufengqin (手风琴, “hand organ”) more acutely than most. He now runs one of Shanghai’s last accordion shops, and has had to diversify into pianos and violins to keep his business open on the city’s prestigious Jinling Road.

“The 1960s was the start of ‘accordion fever’ in China,” Dai tells TWOC. “The military’s song-and-dance troupes, the ‘culture worker’ propaganda groups touring around the countryside…almost all of them had one.

“Of course,” he adds, “other Western instruments were banned.”

In 1985, a bemused Chicago Tribune also pointed to the Cultural Revolution to explained how a foreign instrument, associated with polka and minstrel shows in the US, was somehow “strik[ing] a chord” with the Chinese. “Two accordion factories, one in Shanghai and one in Tientsin, each squeeze out 35,000 instruments a year to supply the demand” the Tribune reported, quoting an American accordionist who compares China’s then-most popular instrument to the guitar in the West. But if the latter’s ubiquity in American music can be traced to the protest movements of the 1960s, the similarities with accordion may be greater than anyone realized.

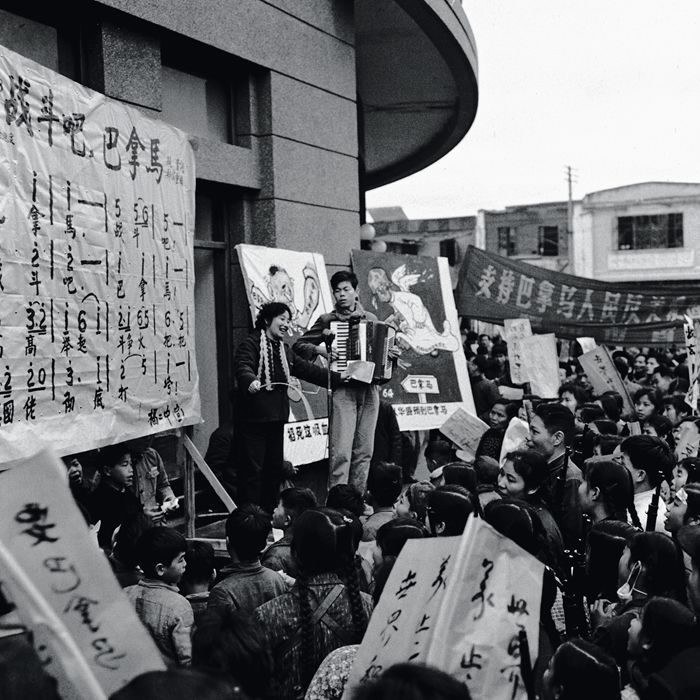

Accordionist Bing Xin plays at a rally in support of Panamanian students in the 1964 Panama Riots

A relatively recent invention, the accordion was patented in 1829 by an Austrian mechanic, and was briefly beloved by the European middle classes due to a fad for mechanized innovations in the industrial age. But the accordion lacked the advantage of a classical canon or patronage by well-known composers that could have sustained its interest among the elite.

According to music historian Helena Simonett, when the modern symphony orchestra and music syllabuses began to be codified in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the accordion continued its fall from favor. In the United States, it was associated with undesirable southern and eastern European immigrants, and cheap vaudeville acts; in Nazi Germany, whose leaders deemed it only “good enough for peasant dances,” the accordion was rejected by national repertoires and troupes. An 1877 New York Times editorial referred to “the so-called musical instrument variously known as the accordion or concertina…a favorite instrument of the idle and depraved.”

Among the working class, on the other hand, the accordion’s “uncomplicated and cheerful sound” and “ease of transportation and storage” made it a mainstay at social gatherings among the urban and rural poor, writes Simonett. Its move to the factory worker’s break rooms, strikes, and political rallies was a natural one. Perhaps due to its importance to Russian folk music, Bolshevik rallies made comprehensive use of accordionists—including a young Nikita Khrushchev, though this claimed was later questioned—to provide entertainment, boost morale, and spread political messages among the masses.

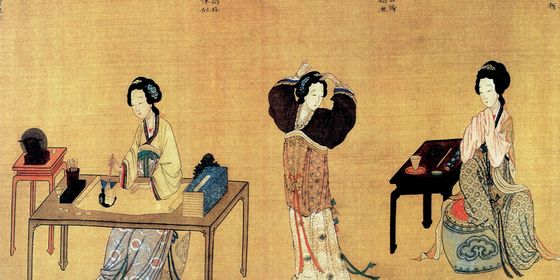

As with many Western inventions, the accordion originally came to China via Japan and in tandem with the late 19th-century educational reforms that swept both countries. China’s first accordion manual, Shoufengqin Jiaokeshu, published in 1905 by The Commercial Press, recommended its introduction into private Confucian academies: Traditional instruments were on the decline, but the accordion could “make the private school a place of music and fun…music is not something trivial, but effective for maintaining community.” Compared to the piano, the accordion was more suited to the modern classroom because it was cheap and easy to store, and optimised for playing Western as well as traditional Chinese music.

But Chinese intellectuals, as Europeans elite had before them, soon dismissed the accordion as a “toy.” It was the Communist Party that was ultimately responsible for preserving the instrument. Long before state-run song-and-dance troupes were formalized by Mao Zedong’s “Propaganda Teams of the Red Army” address in Jiangxi province in 1929, the Party used the humble accordion as a means to spread its political messages. In Kenneth Ore’s memoir Red Azalea, the author recalls working as an underground CCP recruiter in the Republic of China when police grew suspicious of a variety show he’d helped organize, featuring the accordion. “Only Russians and Chinese Communists use accordions,” they alleged, to which Ore replied that the instrument “didn’t carry a proletarian trademark.”

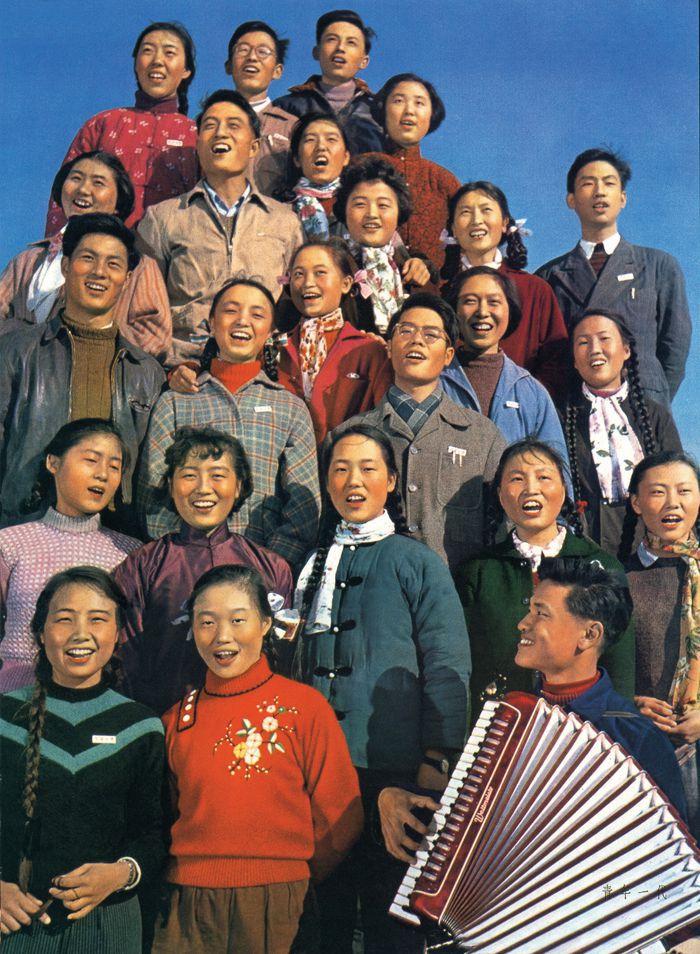

Photo of a Shanghai youth choir accompanied on accordion in the 1950s

He was wrong. Music historian Yin Kee Kwan notes that the accordion was employed by thousands of propaganda troupes—renamed wengongtuan (文工团, “art-worker troupe”) from Mao’s initial xuanchuandui (宣传队, “propaganda team”)—that took the Party’s message to the countryside throughout the 1940s and 50s. The first full decade of the People’s Republic saw the establishment of state manufacturers in Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing, and both the Accordion Society of China and China’s first accordion orchestra were established in Beijing in the early 1960s.

Soviet song-and-dance troupes (that had earlier undergone their own political purges under Stalin, which the accordion survived) gave regular performances in China, influencing the establishment of the PLA’s own gewutuan (歌舞团) as well as adding Russian folk tunes to the accordion’s repertoire, alongside the “red songs” and Chinese folk music that were arranged.

All that the Cultural Revolution had to do was to dial up this cultural and political history to make the accordion the No. 1 instrument of the masses. Shopkeeper Dai believes that the 60s “accordion fever” owed to more practical than political concerns: “It’s portable; it can be stowed anywhere; it didn’t use electricity, so it could be played in remote villages; its repertoire was diverse; it could play solos, as well as harmonies and chords, unlike small Chinese instruments such as the erhu, so it worked like a one-man band.”

But historian Richard Kraus has written that, compared to the piano, the accordion did have a “proletarian” rather than “bourgeois” symbolism, if only because it was ubiquitous at mass gatherings. On the Chinese chapter of Accordions Worldwide and Baidu’s “accordion forum,” former propaganda workers recall being enthusiastic welcomed around the country by entertainment-starved audiences in some of the remotest places of China.

“Most villagers at the time have never seen an accordion, couldn’t imagine that this object carried on a person’s back could mimic the sound of a train, and they were glued to their seats as soon as the overture sounded,” wrote one accordionist of the propaganda solo “The Train Flies Toward Beijing,” once part of his regular set list. “I still think about their applause from time to time…whenever the kids in the area saw me they’d shout, ‘We’re arriving at Beijing Station! We’re arriving at Beijing Station!’”

Many of these musicians found work as teachers in state-run youth recreation centers (少年宫, “Children’s Palaces”) from the 1980s through to the early 90s, when the Tribune got wind of the instrument’s popularity. It became the instrument of choice for parents wanting their children to learn a modern Western instrument, but with neither the money nor space for a piano. Dai adds that cultural memory also played a role: “These parents grew up listening to accordion; they know Western songs through the accordion.” The most successful, former Dalian Garrison Wengongtuan member Jiang Jie, even became a minor celebrity with his own series of cassette tapes, a music school in Beijing’s Xidan district, and a branded teaching syllabus.

Accordions Worldwide reports that China still boasts the world’s largest number of accordionists—and on July 24, 2017, 2,260 accordionists from 20 countries played together at a Shenzhen accordion festival to set the Guinness World Record for Largest Accordion Ensemble (the last three years’ records were also set in China). The Jiang Jie Accordion Academy, however, is now Jiang Jie Piano City, a music store.

Dai says this is an inevitable change, as the piano has more prestige, while the accordion lacks a distinctive repertoire beyond re-arranged piano music and outdated red songs. “Our syllabuses ought to focus more on music unique to the accordion, like tango perhaps, or encourage musicians to write original compositions,” he says. “Only then can the instrument be popular again.”

He isn’t too worried about business, however, as a new group of customers is beginning to patronize the shop. “Retirees—middle-aged and elderly people who have more time on their hands and decide to pick up an instrument—often go for the accordion,” he says. “They grew up with it, have a lot of memories of it, and now play it when they gather in the street or dance in the square to relax, to be happy, to get enthusiastic.”

It’s not bad epilogue for an instrument of the idle and depraved.

The People’s Squeezebox is a story from our issue, “Fast Forward.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.