A migrant community’s 14-year fight to educate its youth

It’s still dark at 6:20 on a winter’s morning as parents drop their children off at Tongxin Experimental School’s green-painted gate en route to work.

As the school’s basketball court fills with the shouts of 200 students, planes from the nearby Beijing Capital International Airport fly low overhead, their drone loud enough to drown out the children’s laughter.

Tongxin is one of a number of “community schools” in China that try to offer an education to the children of its “floating” population, often in the face of overwhelming odds, and with a future as precarious as those of its pupils.

The last several decades have drawn 234 million people from China’s countryside to its cities. They have an estimated 103 million children, comprising 38 percent of all Chinese children, the National Bureau of Statistics reported in 2015. The majority are “left-behind” in the care of family members in their hometowns and villages, yet some 34.3 million accompany their parents to the city.

“The flow of migrant workers in China is a pendulum,” Professor Han Jialin of the Beijing Academy of Social Sciences told the Legal Daily in 2012. “When the city’s industry needs them, they use the system to draw them in. When we don’t need them, they squeeze them back out. In the planning process, of course, they will not consider their children’s studies.”

Tongxin’s motto encourages students to “Grow into a person with knowledge and integrity”

It is notoriously difficult for migrants or their children to receive public services in the city, like education and healthcare, without a local household registration (hukou). To register at a Beijing public school, parents must provide five to seven certificates, including a temporary residence permit, housing lease, immunization papers, and employment contract.

Ministry of Education numbers show that 2.25 million primary school-aged migrant children were outside the public school system in 2017. In Beijing alone, 31 percent of children under 15 do not have local hukou. Around 80,000 school-aged migrant children, or one in six, attend private schools which are more flexible; a further 25,000 do not attend any school, according to 2015 municipal data.

Occupying the legal gray area in between are schools like Tongxin—run by community activists, often leasing land from village governments, but not officially licensed by municipal authorities. Tongxin is currently housed in Picun village, once a rural settlement of just 1,000 in the outskirts of Beijing’s Chaoyang district. Since the 1990s, rural migrants have been arriving in the village, drawn by the affordable rent, making Picun’s population swell to around 20,000.

Among them was Tongxin’s co-founder Wang Dezhi, who came from Inner Mongolia at age 18 to find work in a kitchen, before starting a musical group called the New Worker’s Art Troupe. Their 2005 hit “All Workers Under the Sky Are One Family” sold 100,000 copies, earning the group 75,000 RMB in royalties, and a unique opportunity to put their lyrics into action.

“Rather than split up the royalties, we thought we would use the money to solve a real problem in our community,” Wang told TWOC. “There were many people with children here. And although we didn’t even have girlfriends at the time, we thought we might have children one day, too.”

Teacher Xie holds a lunchtime rehearsal for the school’s music group

The sum was used to rent an abandoned factory. “There were wild grasses everywhere and a crude toilet. Everything was broken down,” said Tongxin’s current principal Shen Jinhua, who, as a senior at China Woman’s university, had joined a group of 100 volunteers to build the school from the foundations in the summer of 2005. “We laid a cement floor overnight.” Teams headed to a nearby pig farm, vegetable fields, and timber mill to recruit students from kindergarten to the sixth grade.

While male volunteers and workers laid the roof, female volunteers began teaching. The first winter, when the radiator froze, Wang sprayed it with a hose, explaining matter-of-factly to a visiting researcher, “If the ice doesn’t melt quickly, the heater will freeze, and the children will freeze.”

Tongxin took in students rejected by or unable to afford other schools. One parent recalled Shen simply telling her, “Pay what you can.” Tongxin also accepted students with disabilities, such as a pair of siblings with brittle bone disease, who attended at no cost. A school document reported that, from 2005 to 2012, over 2,000 students received various levels of fee reduction and scholarship support.

“We are serving the workers’ children,” explained Wang, whose own children now attend Tongxin in the first and fifth grades. “If we don’t accept them, where do these children go to school?”

Shen stayed on after graduation, expanding Tongxin from one building to five, each built with loans. “The way to deal with a thousand changes is not to be changed,” she recited a line from the Daoist text Dao De Jing. “Stability is the foundation of a school.”

But for schools like Tongxin, stability is a luxury. On a warm June day in 2012, a “Suspension Notice for School Shutdown,” issued by the local education and health division, informed Tongxin that it had not met standards for “housing safety, fire safety, electrical safety, and healthcare,” and lacked the “qualifications for running schools according to regulations.”

Some students squeeze in a quick card game before the bell

A public appeal was circulated to rally support for Tongxin’s 658 students and 32 teachers. In July, CCTV host Cui Yongyuan, and a number of lawyers and scholars, joined in calling the Minister of Education to preserve the school. The eleventh-hour outcry, aided by celebrity, ultimately spared Tongxin from forced closure.

Tongxin’s classes began again in August, but a number of other schools in the same township were not so lucky. The city offered to relocate 1,500 students into a public school, but others were simply dispersed—leading to an influx of students to Tongxin, whose enrollment reached an all-time-high of 900 students in 2013, cramping classrooms and straining resources.

And then the pendulum reversed. In 2014, the central government announced the National New Urbanization Plan (2014-2020), which advocated “strictly controlling the population of megacities” and “making painful efforts to contain Beijing” by “controlling people by industry” and “managing people by housing.”

Aiming to cap its population at 23 million by 2020, Beijing officials raised the threshold for entry into public schools, with some districts requiring original documents proving social security payments for three years, rental tax payment certificates, and employment within the school district.

Alongside increased restrictions around employment and housing, the policies were effective at pushing floating families out of the city. An investigation by the Legal Daily found a 37 percent decline in migrant students enrolled in Beijing schools between 2013 and 2014.

A sixth grader hunches over a problem on multiplying fractions

“Of course we want to become legal,” Shen told TWOC, “then we can peacefully run the school and educate our kids. But this is difficult.” While Beijing authorities granted licenses to 63 migrant schools from 2003 to 2006, they then abruptly stopped—making all migrant schools thereafter easy to arbitrarily close. The number of Beijing migrant schools dropped from over 300 in 2006 to 127 in 2014, according to NGO New Citizen Project. Even the Zhiquan School in Changping district, a licensed school, received an order to close in 2017 for operating in an illegal building.

Tongxin’s 20-year land lease from Picun will expire in 2025, and there is no guarantee of renewal. Indeed, not only Tongxin, but the village itself remains at constant risk of full or partial demolition. After a deadly fire in November 2017, Beijing municipal government launched a 40-day campaign to demolish 15 square miles of “unsafe” buildings that forced tens of thousands of migrants from their homes. Many who were unable to find new housing had to return to their hometowns.

Shen estimates that one-fifth of her student body leaves each semester, and a little less than that figure arrives in their place; she described her schoolyard as a harbor for the children’s wind-tossed childhoods, flung between strange cities and estranged hometowns.

Zhao Yun, a former Tongxin teacher, agreed. “The children here are passionate, open-minded, undefended, firm and brave…” China Youth Daily quoted him saying in a school assembly in 2014. But though Zhao was voted a “favorite teacher” by the student body, the Peking University graduate left the next semester for a better-paying job, out of respect for his family’s wishes. Tongxin teachers make between 3,000 and 4,600 RMB per month, rendering retention of university-educated teachers “impractical,” according to Shen. Instead, she focuses on developing the skills of its longer-term teachers, many of whom are middle or high school graduates.

Students head to the school gate for pick-up at the end of the day

While the curriculum and teaching materials of unlicensed schools are not standardized, Tongxin offers core studies of math, Chinese, English, PE, music, and art. Volunteers also teach photography, TV broadcasting, and swing dance. In addition, Shen has organized schools trips to the aquarium, the Beijing International Art Biennale, the cinema, and a science museum. “We hope that through these diverse activities, children can broaden their perspectives,” said Shen. “We believe that only with these wider horizons can we open their imaginations about the future.”

Yet Shen recognizes that Tongxin cannot reverse inequities that begin at birth, and which extend far beyond the schoolyard. “One year we picked some of our brightest and most involved students to attend a summer camp at a university,” Shen admitted. “When they arrived, they felt that they were behind their peers.”

Studies find that continual adjustment to unfamiliar environments, a lack of strong social relationships, and discrimination in urban schools contribute to lower self-esteem and higher rates of depression for migrant children. A 2018 study led by psychologist Hu Hongwei at Renmin University found that, while left-behind children tended to “internalize” problems by becoming withdrawn, migrant children were more likely to “externalize” problems through hostile behavior.

Migrant youth are disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system. One juvenile district court in Beijing revealed that the criminal offense rate for migrant youth was three times higher than local youth in 2005. In one Shanghai district court, 95 percent of juveniles arrested between 2008 and 2010 were migrants.

For fear that parents would send their children home, Shen hasn’t raised Tongxin tuition of 2,000 RMB per semester, even as similar schools have increased theirs to 5,000 RMB. However, the fees are barely enough to cover operating costs. “The classroom walls, the electrical wires, the awnings… this is what we’re stressed about these days.” To make up the difference, she accepts secondhand beds from international kindergartens, rents the school’s yard for commercial shoots over the weekend, and brings the student choir to perform at corporate galas to raise funds.

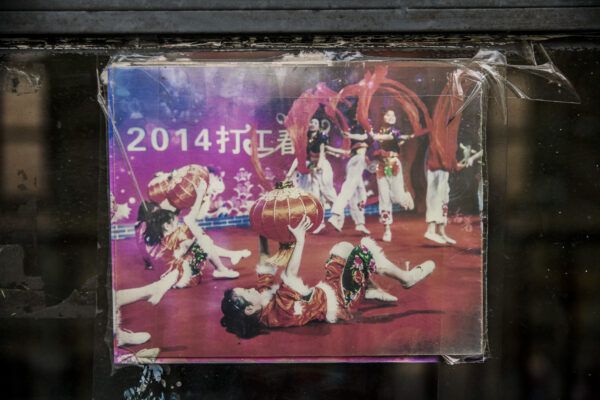

Students performing at a worker’s spring festival gala in 2014

As questions of urbanization hover over the country, the education of migrant children is repeatedly sacrificed at the altar of population control. Although Shanghai reduced the “five licenses” requirement to two licenses in 2008, making it possible for many migrant children to enter public schools, it began increasing the amount of required paperwork again in 2014. By 2016, the number of students in public schools returned to the level of 2007.

Cities such as Guangzhou and Suzhou have introduced a points system for migrant children’s public school eligibility in recent years, contingent on factors such as owning local real estate and paying social security fees, effectively excluding the city’s poorest.

In 2003, Premier Wen Jiabao visited an elementary school for migrant children in Beijing’s Shijingshan district, chiseling onto the blackboard: “Under the same blue sky, we grow and progress together.” Last year, however, the district’s largest migrant school was ordered to close its gates to around 1,700 migrant children after operating for 20 years.

The central government’s Compulsory Education Law, revised in 2006, reaffirmed its legal responsibility to “provide equal conditions for compulsory education for children of migrant workers.” Yet these good intentions fail in the face of lack of actual resources and actions, leaving administrators like Shen to attempt to draw miracles from thin air.

“When we meet a mountain, we cut a path; when we meet water, we build a bridge,” she sighed. “We can always cross.” Ultimately, though, Shen waits for the day when “Tongxin no longer needs to exist,” when the country’s educational resources will be open to all.

Parents and caretakers take students home along the main road of Picun village

Class Action is a story from our issue, “Tuning Up.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.