An annual festival celebrates the culture of Shandong’s “birthplace of kites”

Weifang, the “world kite capital,” is believed to be the birthplace of kites. Each spring, in April, people in Weifang fly them to celebrate the Weifang International Kite Festival.

The World Kite Capital Commemoration Square (世界风筝都纪念广场) is a landmark built in 2006 and dotted with kite-related features. In front of the square stands a 28-meter sign from the International Kite Federation; 12 bronze mascots of past festivals and plaques explain the history and production of the ancient plaything. To learn more about kite culture, one must visit the Weifang World Kite Museum (潍坊世界风筝博物馆), south of the square.

A two-story building with a roof in the shape of Weifang’s representative dragon-headed centipede kite, the museum covers 12,000 square meters and 12 exhibition halls. Here visitors can see more than 1,000 kites of different styles and learn about their history and art of manufacturing.

The ancient philosopher Mo Zi (墨子) is believed to have been the first kitemaker. The pre-Qin (before 221 BCE) book Han Feizi (《韩非子》) recorded, that 2,000 years ago, Mo Zi spent three years making a kite with wood, only for it to fail. Lu Ban (鲁班), one of Mo’s pupils, replaced the wood with bamboo and managed to make a magpie-shaped kite which could fly for three days. It was recognized as a success; today, a bronze sculpture of Lu Ban, “The Father of Kites,” stands upright on the World Kite Capital Commemoration Square.

Yangjiabu Grand View of Folk Art Park, Weifang

Northern people called kites yuan (鸢, eagle), or zhiyuan (纸鸢, paper eagle), while southerners called them yao (鹞, sparrow hawk). During the Five Dynasties (907 – 960), a man named Li Ye attached a bamboo flute to make a musical kite; the name fengzheng (风筝), or “wind zither,” was then adopted.

Among their many uses, kites were deployed in war to deliver messages. Once gunpowder was invented, kites were occasionally weaponized. During the Song dynasty (960 – 1279), a detonator was flown over the enemy to explode. This primitive missile was called the “bombing-crow kite.”

The main function of kites, though, remained entertainment. After the Sui and Tang dynasties, paper kites flourished. In the Song dynasty, there were competitions, and flying kites on Tomb Sweeping Day became a folk custom. People would cut the string once their kite was high in the sky, believing that one’s illness and bad luck would fly away with it.

In the Qing dynasty (1616 – 1911), famous littérateur Cao Xueqin detailed how young nobles flew kites in his classic novel A Dream of Red Mansions, which gave insight into the popularity of the hobby in that era.

Zheng Banqiao, a famous painter in the Qing dynasty, described a scene of Weifang citizens flying kites in his poem “Memories of the Wei County”: “The paper flowers flying in the sky, just like countless snowflakes.”

Kites at the time fell into two main categories: the Old Wei County Kites (老潍县风筝), which were mainly made and painted by local literati and craftsmen, and the Yangjiabu Kites (杨家埠风筝), influenced by woodblock prints. In today’s Yangjiabu Grand View of Folk Art Park (杨家埠民间艺术大观园), there is a Yangjiabu Kite Museum where visitors can learn more, and even make a kite in the workshop. Today, around 5 million Yangjiabu kites are made each year.

Entering the 20th century, the development of Chinese kites skyrocketed under the New Culture Movement. People not only flew kites as a leisure activity, but also appreciated the craft, and held professional competitions. These competitions promoted the revival of the industry. Just before Tomb Sweeping Day in 1937, a bazaar in Weifang sold nearly 10,000 kites every day and annual sales that year reached 200,000.

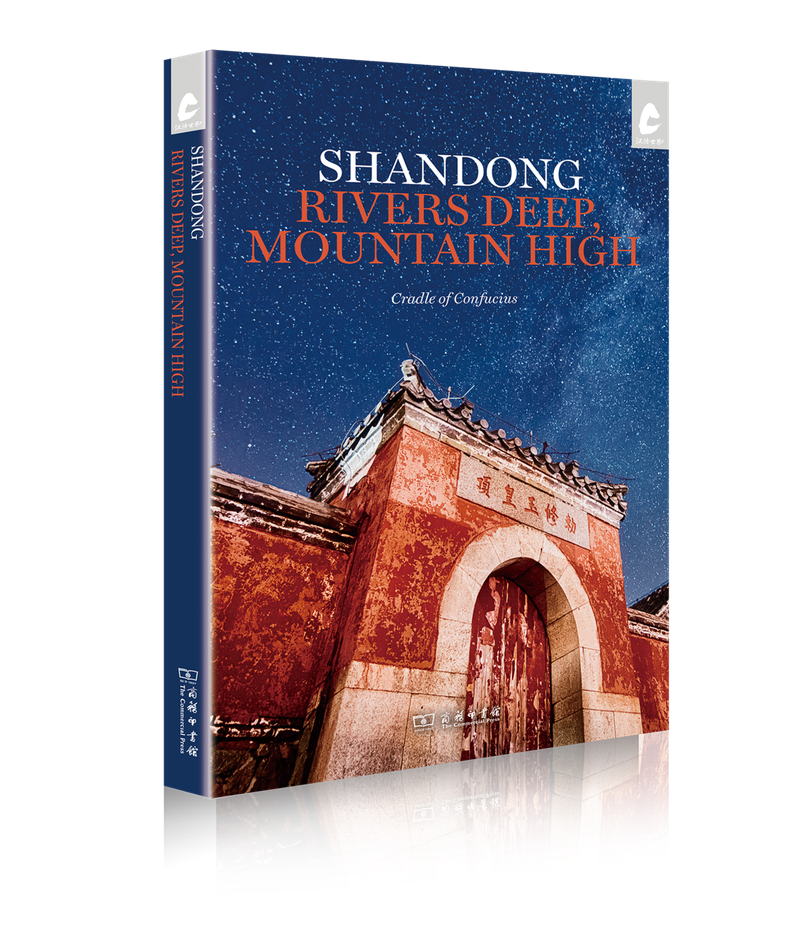

Cover image: the Weifang World Kite Museum

Excerpt taken from Rivers Deep, Mountain High, TWOC’s newest guide to Shandong. Get your copy today from our online store.