TWOC attends the Future of Go Summit, the epic clash between human and AI that ended humanity’s 2,500-year dominance of the game

One hour into the final match at the Future of Go Summit, shouts and popping flashbulbs suddenly disrupted the silence that had settled over the audience at the Wuzhen International Convention Center. Nie Weiping (聂卫平), hero of the 1980s’ China-Japan “Super Matches” in Go, had arrived to commentate. Later, some would say he was there to sound the death knell for the game he’d helped popularize.

“Black has already won,” he said, before the applause had even died down. It was 11:30 a.m.; and only the 38th move.

The summit, held in the last week of May, had been fraught with emotion, laden with apocalyptic predictions on social media, and immense pressure fanned by Chinese and international media. Through it all, the player now on Black had held unperturbedly onto their winning streak. This was AlphaGo, the AI program built by Google’s DeepMind lab. In 2016, it had become the first machine to best a top-ranked professional human player in a live match of the 2,500-year-old Chinese game on a standard 19-by-19 board. Now, this would be its last match before retirement.

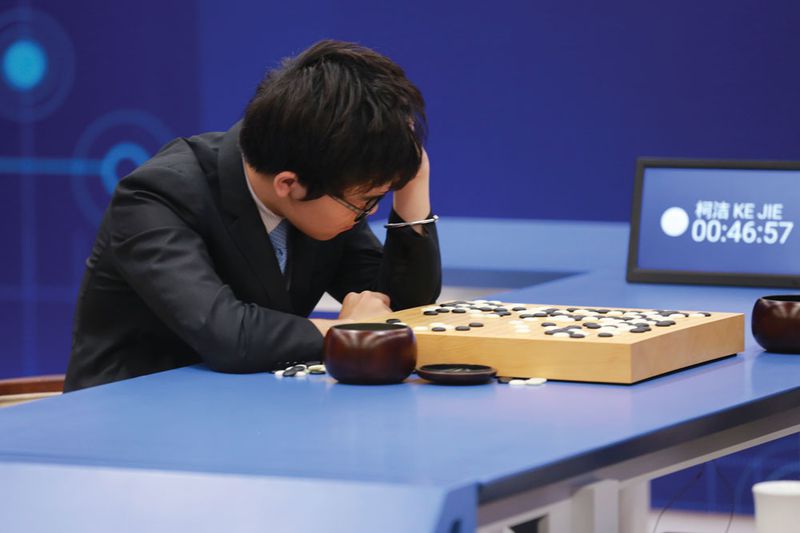

AlphaGo’s opponent was 19-year-old Ke Jie (柯洁), child prodigy, the world’s No.1 ranked Go player for the last two years. But after entering the competition in the unfamiliar position of the underdog, and losing his two previous matches at the summit, Ke remained stonily silent, even as the crowd reacted with a mix of amusement and relief at Nie’s pronouncement.

Ke Jie vs AlphaGo (VCG)

It was a curious end to a week—some would say years—of emotional strife in which Ke, the Go community, fans, and international media had spent the lead-up to the final match.

Winning his first national competition at age 10 and first world title at 17, Ke had become the poster boy of China’s new generation of elite Go players since the country’s return to dominance in the game it had invented, a process that started with Nie’s victory decades before. Yet as the summit neared, Ke was given the monumental task of representing humanity’s superiority to AI. Small wonder that he self-deprecatingly announced, at a press conference prior to the tournament, that he would “play for the best and prepare for the worst.”

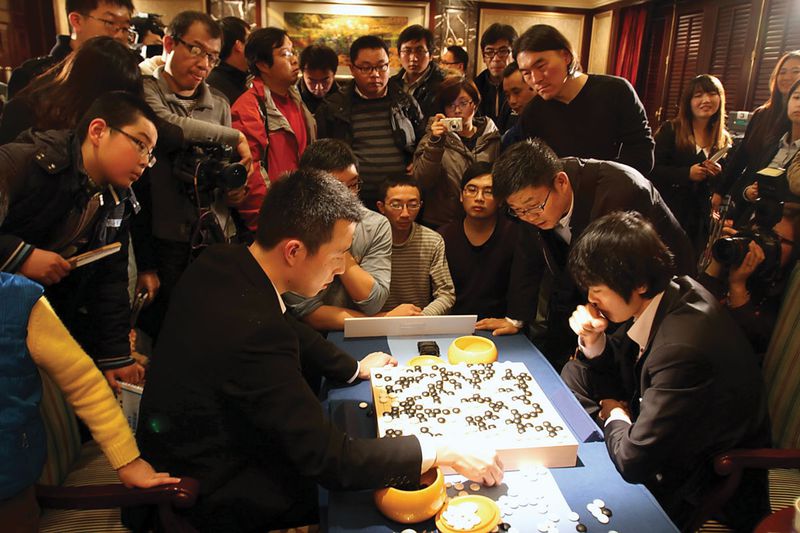

Gu Li (古力), Ke’s friend and former No. 1 player in the world, gave Ke better odds: “Ke has just 10 percent chance to win one game of all three,” he predicted to Shaanxi newspaper Chinese Business View. Fans jokingly rebutted that Ke’s only chance would be to unplug the machine.

At 10:30 a.m., May 23, the first of three Future of Go matches between Ke and AlphaGo began. Ke played Black, which meant he moved first. At the seventh move, viewers in the commentary room let out a gasp: Ke had played a “3-3 point” move, a risky strategy typically saved until the middle of the battle. There is currently only one player in the world known to risk this move as an opening gambit: AlphaGo.

(VCG)

In January, under the pseudonym “Master,” AlphaGo had played 60 online games against several of the world’s top players including Ke, regularly playing the “3-3 point” as an opening move. At first, players thought the AI must have lost its mind. After AlphaGo won all 60 games, they couldn’t stop raving about its methods.

The ancient game of Go is no stranger to innovation. Known as weiqi (围棋, “encircling chess”), it has been played in China since at least the sixth century BCE. Numerous masters, first in China and then Japan after the ninth century, have improved upon the rules to the extent that it’s now impossible to compare the skills of an ancient master to a modern champion. However, the essential object is to surround a larger area of the board than the opponent with stones of the player’s own color.

Modern Go is played on a board crisscrossed by 19 horizontal and vertical lines, forming 361 intersections—essentially infinite possibilities of play. Winning relies on an intuitive ability to recognize a good move, rather than mapping out future moves, one of the reasons why the AlphaGo matches were so highly anticipated (though AI had already beaten humans at other complex games such as chess).

Legend has it that Go’s invention came via two immortals who instructed the mythical king Yao to use it to teach his rakish son the merits of patience and calm reason. The chessboard represents an ancient view of the universe: Round stones representing heaven, a square board for earth, yin (black) and yang (white) forces acting out the processes of life amid the intersections that symbolize the days of the year.

At the second Future of Go match between Ke Jie and AlphaGo, Ke resigned while most of the media was at lunch (VCG)

In the Tang dynasty (618 – 907), the heyday of Go, the game had a more secular status among the four main accomplishments of the Confucian scholar, in addition to painting, calligraphy, and playing the seven-string zither. There were Tang officials solely responsible for playing Go against the emperor. Confucians believed that Go-playing cultivated moral character, teaching equanimity in the face of pressure and loss.

And yet AlphaGo is now changing the way human players play the game. “When we learned Go as children, the teacher would never allow you to play a ‘3-3 point’ so early,” professional player Xu Ying commented during the fateful first match. Ke was even more admiring afterward: “AlphaGo is changing our original perception of Go…no move can’t be played.” Ke admitted that he was imitating AlphaGo’s play intentionally, to see how it would deal with its own strategy.

Still, up until a match-up between AlphaGo and South Korean master Lee Sedol in Seoul in 2016, the Go community, as well as those loathe to see machines triumph completely, were hoping that Go’s complexity could still prove a point in favor of human understanding.

Yet in one baffling moment in the third of five matches in last year’s Seoul tournament—with AlphaGo leading Lee two matches to none—the AI stunned its opponent, commentators, and 280 million live viewers by playing a move that seemingly defied logic, as well as its own calculation of the odds. There was just a 1-in-10,000 chance that a player would make that move. The AI went on to win the match, proving that its algorithm could incorporate human-like intuition, instead of making predictable moves based on the millions of previous games its memory had been fed.

The media’s hype machine went into overdrive at the possibility of an AI that thought for itself. The result also created an unprecedented amount of pressure for Ke, one he partly cultivated himself. In China, Ke’s public persona toes the line between “outspoken” and “bratty”; just a year ago, he criticized other players for deifying AI. Prior to the match in South Korea, Ke voiced support for Lee: “In 1997, the chess-playing computer ‘Deep Blue’ beat Garry Kasparov, while Go has been resisting for so many years. [Go] is already great even if [Lee] loses the game.” But when AlphaGo finally won, Ke proclaimed on social media, “Even though AlphaGo defeated Lee, it can’t defeat me.”

Wang Zhi depicted watching Go at Mount Lanke, Zhejiang (Fotoe)

The brazen declaration went viral online, and increased Ke’s Weibo following from 18,000 to 420,000 in less than a week. The belief grew that if AlphaGo could defeat Ke as well, it would prove that AI had now outclassed humanity in the field of Go.

The AI was now, however, easily seeing through Ke’s “3-3 point” gambit. As the match wore on, Ke developed a noticeable tic—unconsciously leaning forward, his body hunched toward the board, before making any move. As the hours passed, he leaned more often, and hunched farther, longer.

The turning point appeared at the 54th move, when AlphaGo placed its white stone onto a very unexpected position; once again, the whole Go-watching world was immediately thrown into confusion. The observation room buzzed with chatter. Ke leaned forward. But he was probably the first to understand what had happened. “I was shocked…It would never happen in a game played by human. But later I figured out it was a good move,” he said after the game.

Finally, four hours and 15 minutes after the game began, Ke lost by half a point, the smallest margin possible. But AlphaGo is programmed to seek the surest route to victory, instead of the largest margin of winning. Looking back, Ke never had a chance since the first minute of the game.

“Lady Playing Go,” a silk painting from the Tang dynasty (Fotoe)

It was a very different Ke who attended the press conference after the first match. Gone was the braggadocio—he was now “fully convinced” of AlphaGo’s ability. “It was a completely different ‘person’ compared with last year,” he said. “Last time, it was still close to human. But now, it has become a god of Go.”

Some believe that this god is a benevolent one. There’s no question that the “Great Human-Machine Tournament,” as Chinese media dubbed the event, has drummed up interest that in a sport whose profile had “dampened” within China in recent years, according to retired player Yang Rong, captain of Ke’s team in 2013. “In the 1980s China saw a period of ‘Go fever,’ but it seems that in the 90s, everyone became too busy trying to get rich,” Yang told TWOC.

Ironically, 80s Go fever had itself been precipitated by a decline in China’s mastery of the game. For much of the 20th century, the game had been dominated by a historic rival, Japan (it’s still known to the world by its Japanese name). In the early years of the Republic of China, Japanese player Takabe Dohei had bested every Chinese opponent, and salted the wound by declaring that even the best Chinese were merely at the level of 1 dan, the lowest professional rank in Japan. It was a bitter pill for Chinese to swallow, made even more painful by Japan’s occupation of China in the 1930s and 40s. From then on, the nation’s prowess at Go became a point of patriotism.

From 1939 to 1955, the top Go master in the world was Fujian-born Wu Qingyuan (吴清源). But he did nothing to resolve the politics of the game, since he had obtained Japanese citizenship before the war. In 1959, Chinese Foreign Minister Chen Yi, a Go aficionado, declared that, “when the country rises, Go develops. When the country is in decline, Go declines as well.”

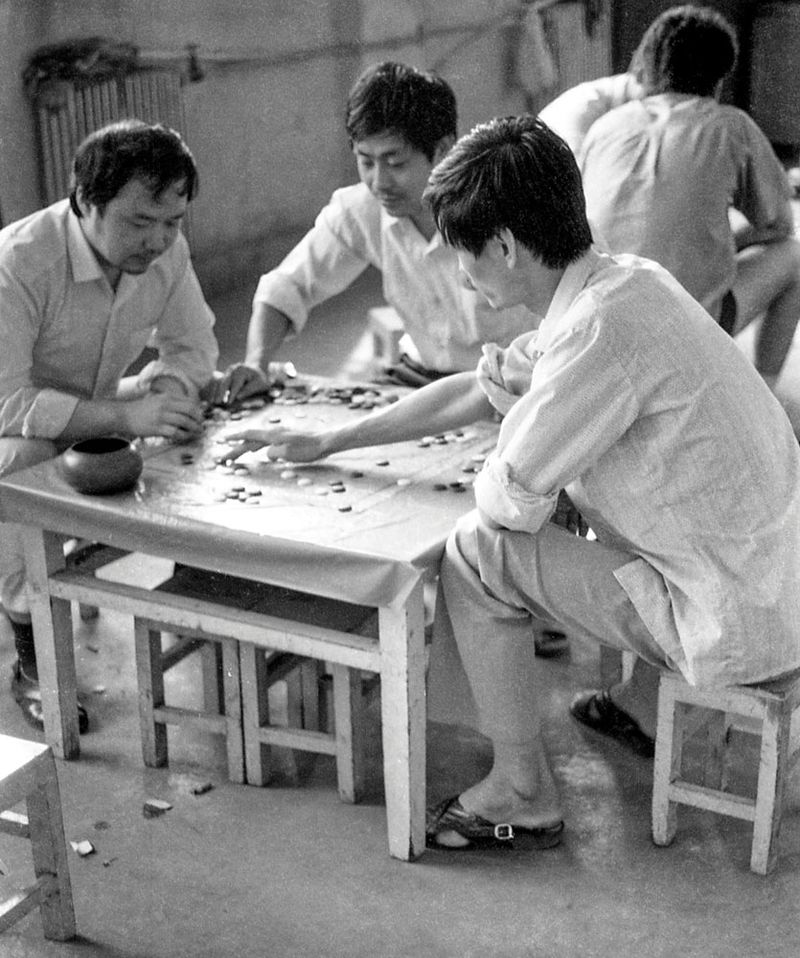

Players preparing for a Go contest in the city of Pingdingshan during the mid-90s (Fotoe)

Chen proposed cultural exchanges, known as “Go Diplomacy.” This was a misnomer. In 1960, the Japanese Go delegation visited China and played 35 games, among which China only won two. One year later, the Japanese delegation revisited, and Ito Tomoe easily defeated Chinese master Liu Dihuai—even having time to leave the board to “watch flowers and birds” outside, one opponent noted. The failure was regarded as a national humiliation.

In 1984, the China-Japan Super Matches used the knockout format with six to nine players on each side. The performance of Nie Weiping, then in his 30s, could only be described as legendary, beating seven top Japanese players, accumulating an 11-game winning streak, and winning the competition almost single-handedly—defeating all his opponents twice. It’s as if China’s Guangzhou Evergrande football team were to beat Bayern Munich, Real Madrid, Barcelona, Manchester United, and Juventus all in a row.

For his extraordinary performance, Nie was awarded the title “Sage of Go” by the Chinese National Sports Commission: Go fever had officially begun. Before 1984, Japan’s population of 100 million had around 600 professional players and over 12 million Go buffs, whereas China, with 10 times the population, had about 100 professionals, among whom only four had the rank of 9 dan (highest professional Go rank). In 2000, China’s Go Universe magazine reported that there were around 20 million professional and amateur players. In 2005, seven-year-old Ke was sent to the Nie Weiping Go Dojo, a training school founded by the former champion.

To Ke’s colleague Yang however, Go fever is partly contingent on a continued sense of pride and dominance in China’s performance. “The public’s interest in Go and the results of professionals are intimately related. The better we do at world championships, the greater the interest in learning Go,” he said. “Though we advocate for the spread of Go and Go culture, though we speak of the joy of Go, first we need Ke Jie and good results at international tournaments.”

The AI that played Ke in Wuzhen was an improved version that had played Lee in 2016. According to Demis Hassabis, CEO the machine is driven by a new and more powerful architecture. Rather than regurgitating tactics generated by humans, it can now learn almost entirely from playing against itself.

The new version added three handicap stones to the 2016 AI, to make the two players’ ability roughly equal. It’s an unbelievable gap that rarely appears between top Go players. As Ke put it, it’s like allowing your enemy to stab you three times first in a duel. At midnight before the first match, Ke stated on Weibo that, whatever the result, the tournament would be his last against AlphaGo: “I will use up all my passion to fight in the last duel. No matter how formidable the opponent is, I won’t back down! At least one last time.”

Thousands of young players attend a mass Go event in Hubei in 2016 (VCG)

The second match began as scheduled on May 25. Ke described his “blood surging” after the game. Many predicted that Ke might employ the “mirror Go” strategy, when a player plays moves diagonally opposite those of the opponent, creating positions with 180-degree symmetry about the central 10-10 point. Though less exciting to watch, it’s effective. Ke had defeated Fine Art, a Chinese AI developed by Tencent, with the same strategy.

But it seemed as though Ke didn’t want to make the game to become AI against AI. He tried to gain a lead from the very beginning, complicating the play as much as possible. His aggressiveness “pushed AlphaGo right to the limit,” Hassabis tweeted. The crowd was cheered, but as Ke played, he grew more and more solemn. Now and then, he grasped his chest with his hands. “I was very excited. I could feel my heart thumping,” he told the press conference afterward.

It has become almost cliché for AlphaGo’s opponents to effuse about how much their own play has improved through their brush with AI. Fan Hui, three-time European champion-turned-consultant for DeepMind, famously saw his international ranking jump from the 600s to the 300s after several months practicing against the AI. Lee Sedol has reportedly never lost to another human since his 2016 tournament.

In Ke’s case, there was a more palpable disappointment. “Ke Jie truly had a chance to win, but his emotions were in turmoil,” Yang told TWOC. “A person, after all, is not a machine.”

Ke’s perfect performance lasted midway. Though he had managed to complicate play to an extraordinary degree, as the timer wore on, both sides began to move quickly, a situation where machines have the upper hand. AlphaGo was simplifying the game, said the English commentator and player Michael Redmond, “and this was a bad sign for the human player.” On the screen in the press room, Ke was seen nervously clenching his hair.

By the third hour, Ke had used about twice as much playing time as AlphaGo. He was on the verge of losing; within 15 minutes, Ke resigned.

AlphaGo’s creators said Ke had nothing to regret. At the presser, they hailed Ke’s “incredible” performance, saying that AlphaGo’s internal evaluations “agreed with all the moves.” “Nobody can do as well as Ke Jie did in the second game,” said top player Lian Xiao, who partnered with AlphaGo in a mixed-pairs match during the Wuzhen summit.

But Ke’s own feelings were mixed. The second game meant losing the tournament, but it was also the only one in which he had seen the possibility of victory. “Before AlphaGo appeared, I thought I knew 50 percent of the truth of Go. But its birth changed a lot of my life,” he said. “If one percent represents knowing the basic rules, [I feel] my knowledge is just at two percent. And if I can’t win the third match, AlphaGo will be 100 percent to me.”

A match between Gu Li (left) and Lee Sedol during the Samsung Insurance World Masters Baduk tournament in 2012 (VCG)

In the Shuyiji (《述异记》,Tale of Strange Matters), a fifith-century collection of mythical stories, there’s the tale of Wang Zhi, a woodcutter who came across a group of children playing Go in the mountains. Wang sat down to watch for some time, until the children asked, “Isn’t it time you went home?” He then stood up and saw that the wooden handle of his ax had rotted away. Returning to his village, everything looked different; local legend spoke of a man named Wang Zhi, who had disappeared in the mountains hundreds of years ago.

Scholars have read many morals into the story—the unforgiving passage of time or even the danger of Go as a distraction. However, at the close of Ke’s second Future of Go match, it’s Wang Zhi’s utter absorption in the mental intricacies of the game that offers the most appropriate parallels. The game ended while most of the audience was still at lunch, and when the press corps filed in, they found Ke still hunched over the board, reviewing every move that had been played.

“Go is a lonely contest against the self,” Yang told TWOC. “We may all think at a young age that we have what it takes, but you eventually find you can’t always win. Dealing with your emotions and learning from failure is an important part of the process.”

In January, after Ke lost two matches online to AlphaGo as Master, he was reportedly hospitalized. “Human beings spent thousands of years combating, practicing and progressing, but the computer is telling us that it’s all wrong,” Ke told his followers on Weibo, adding that he still had a “last move” that he wasn’t able to deploy against Master.

On May 27, Ke and AlphaGo met for the third and final time, but anyone hoping for a battle royale was quickly disappointed. After just an hour, the former champion Nie broke whatever tension remained, casually announcing what many already suspected: the match was lost, and it wasn’t even lunchtime yet.

Several journalists began drafting post-match reports; no longer concerned with the result, the commentators relaxed by guessing what moves were still available. Only Ke remained immersed in battle, either a lone warrior or tragic hero. It was soon easy to guess which, as he rose and abruptly left the stage for nearly 20 minutes. From backstage, whispers came rippling through the audience that Ke was weeping.

Viewers were at a loss to respond to this anticlimactic though regrettable end to the story, except with clichés and mixed metaphors: “Ke Jie is like a relic of the medieval age…with the steam locomotive roaring toward him,” one viewer wrote. “AlphaGo is too perfect,” Ke himself repeated (Professional player Ali Jabarin had apparently said the same thing to Ke after an encounter with Alpha Go: “It’s too strong…it’s too strong”).

“Go is a trial by ordeal for the personality. The students we teach, often, when they lose, they cry, and when they’re done crying they continue to play. By repetition, it teaches them how to deal with failure, and it tests their willpower,” Yang said. “Ke Jie’s ability to deal with frustration is strong. He’ll bounce back from the loss.”

A team of China’s top five Go players all played—and lost—against AlphaGo in Wuzhen, May 26 (VCG)

There are those who feel that having an unbeatable opponent has made the game less appealing. At an AI conference held in Guiyang during the Go summit, e-commerce tycoon Jack Ma said that developing AlphaGo was meaningless, because he believed the essence of Go was waiting for your opponent to make mistakes. Because AI never makes mistakes, it offers nothing worth watching. Others have said playing Go against AlphaGo was like running against a car or weightlifting against a crane.

“I believe the future belongs to AI,” Ke wrote on Weibo just before the summit began. “But it’s still a cold machine…To it, passion is no more than the heat generated by its high-speed working CPU.”

After the summit, Lin Jianchao, vice-president of the Chinese Weiqi Association, expressed his agreement. “[Google] can decide whether they will play with us. When they choose Go, it’s not out of love for the game but as an experiment…a warm-up. But for us it’s a career, a culture, a heritage…and we must continue to develop [the game] according to new conditions of the times.”

By contrast, Yang appears to think that these new conditions offer room for positive reflection. “To some extent, [players’] abilities can be increased by arduous training…I’ve seen young players take anti-depressants to deal with the pressure,” he said.

Three hundred and fifty children play Go in an invitational tournament held in Beijing on June 24 (VCG)

Yet while these players had good results, Yang said, “there were no ‘masters’ like Nie Weiping and Ke Jie. “It’s making us think, perhaps this method of training has also restricted [the players’] growth. Those moves played by AlphaGo—we all tried them when we were young, but the teachers would scold us, saying, you’re not allowed to play that way.”

DeepMind is already gearing up to position AI as humanity’s teacher instead of opponent. They plan to release 50 “special games,” in which AlphaGo plays itself, and develop a Go teaching tool in collaboration with Ke—but for now, the dethroned champion seems to be taking a well-earned rest.

“The gap between AlphaGo and I is so huge that I won’t catch up with it all my life,” said Ke in an interview with China Global Television Network after the summit. “AlphaGo can see the whole universe, while I can only see a small pond. So, let it explore the universe, and I will just fish in my own pond.”

Two days later, Ke came back to his pond. After defeating a South Korean player in the LG Cup World Baduk Championship, where moves created by AlphaGo were frequently used, Ke posted on his Weibo, saying: “Now I realize that playing Go with humanity is so relaxed, comfortable, and happy…It’s nice to play Go.”

The Alpha and Omega of Go is a story from our issue, “Beyond Go.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.