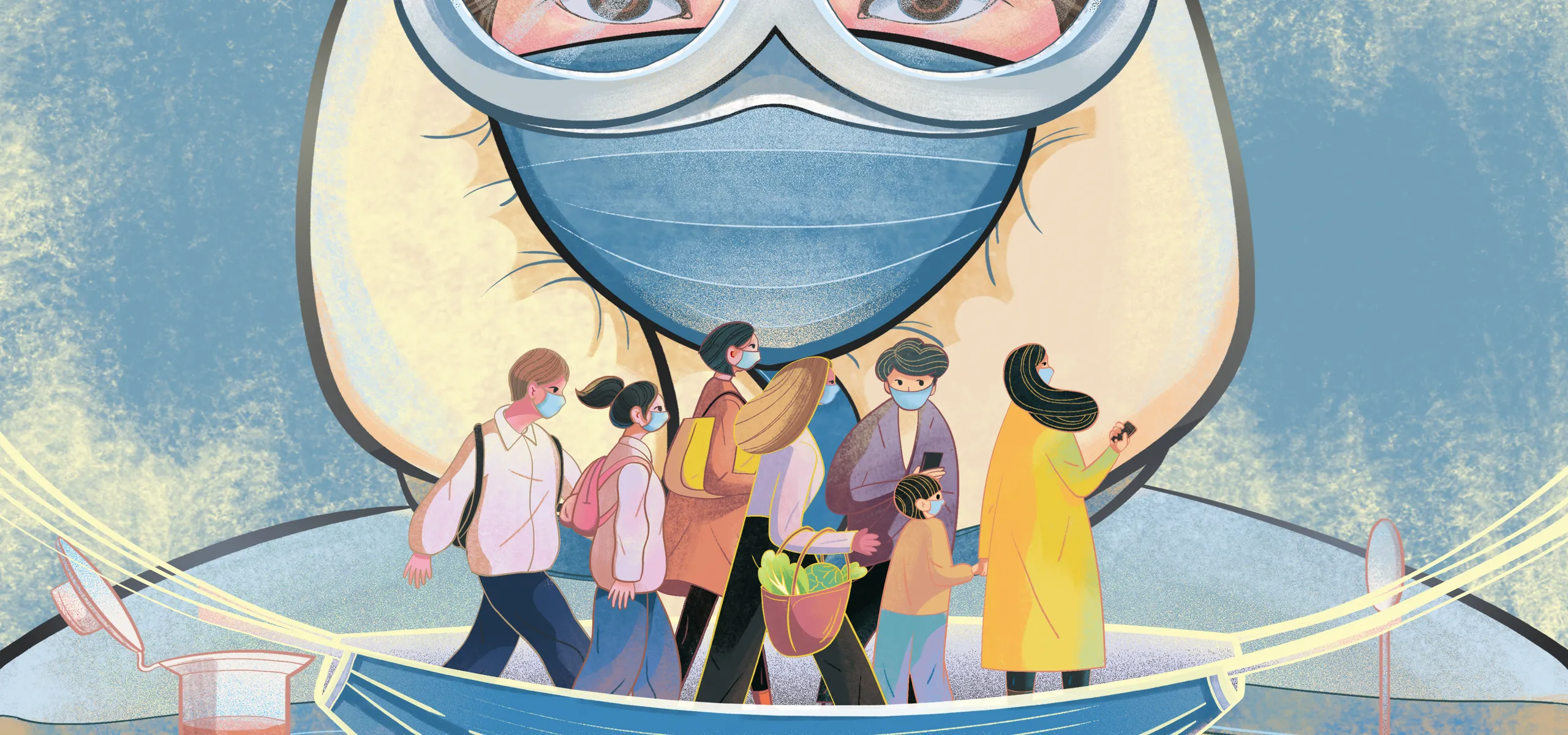

How the epidemic has reshaped life, and how Chinese talk about it

Nearly two-and-a-half years since Covid-19 was detected at a seafood market in Wuhan, the pandemic has touched nearly every aspect of life worldwide—changing people’s attitudes toward food safety, public health, travel, and socializing, as well as popularizing phrases in English like “social distancing” and “flattening the curve.”

In China, which continues to maintain a “zero-Covid” policy, stringent lockdown measures and widespread testing of affected neighborhoods have also made people utterly at home with terms like 清零 (qīnglíng, zero-Covid); 消杀 (xiāoshā, disinfection); 大白 (dàbái, “big white”), a nickname for community workers outfitted in white-colored protective suits; and 核酸 (hésuān), short for 核酸检测 (hésuān jiǎncè, nucleic acid test). When Beijing saw a cluster outbreak in the summer of 2020, it was joked that “您核酸了吗 (Nín hésuān le ma, Have you taken a nucleic acid test)?” had replaced “吃了吗 (Chī le ma, Have you eaten)?” as a standard greeting among residents of the capital.

At the time of writing, Shanghai is nearing the end of the first month of a battle against an outbreak of the highly contagious omicron variant, which has led to China’s strictest lockdown measures to date. With an estimated 400 million people experiencing restrictions due to pandemic control in Shanghai and other parts of China, the pandemic has reshaped how they speak, act, and even eat.

Stockpiling supplies

In the early days of Shanghai’s city-wide lockdown, the shutdown of businesses and delivery channels inside and outside the city made food and other basic necessities into scarce commodities for those who did not stock up beforehand. Across the city, tech-savvy residents got used to setting their alarm at odd hours—say, 5:45 a.m.—to get ready to “snatch” fresh produce from online delivery platforms before they run out.

It is a test of both swiftness and perseverance. Cycling through up to 12 apps on their phone, the Shanghai resident might repeatedly smash the “checkout” button, only to have supplies run out or the app crash due to too many people attempting to order simultaneously. Those who missed out might exclaim:

The Essential Pandemic Language Guide is a story from our issue, “Lessons For Life.” To read the entire issue, become a subscriber and receive the full magazine. Alternatively, you can purchase the digital version from the App Store.