The crafty methods used to weasel out of giving wedding cash, as well as figuring out the right amount

Hu Xiao’s wedding was an embarrassment.

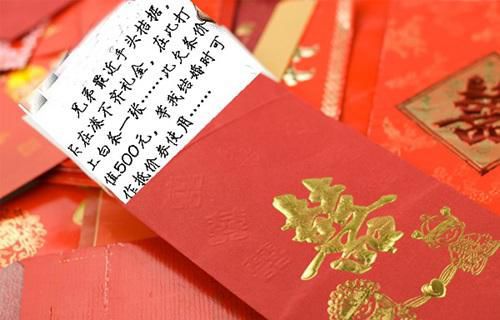

The groom discovered on his wedding day that his colleagues hadn’t bothered to show up, instead sending a collective 500 RMB hongbao (红包, “red envelope” or “red pocket”).

“Was I wrong to invite them?” he asked on WeChat. “How can I return the favor for the six colleagues who sent 500 yuan together?”

Few were sympathetic to Hong’s plight. Many assessed that the absence of his colleagues was a passive-aggressive protest at being invited in the first place. After all, weddings invite obligations—specifically, the hongbao has become a literal tax on friendship that few are willing to extend to workmates as well.

Many Chinese feel anxious about being invited to weddings. The issue is not merely money, but also the relationship and mianzi (面子, face, prestige, reputation) of both sides.

At weddings, guests present fenziqian (份子钱, “one’s share of money to be presented”) in the form of a hongbao to the new couple that expresses their good wishes. The custom originated in the late Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, instead of sending gifts.

The more cash in a hongbao, the closer the relationship between the couple and guest, the more prestigious the guest feels and, also, the more importance the guest attaches to the couple (钱给的越多,客人本身越有面子,也越給新人面子).

But the hongbao are not under-the-table gifts. The amount each person gives is made a matter of public record—after being received at the reception desk, the amount is checked and recorded on a notebook by a trusted person on behalf of the new couple. Thus the amounts can become the subject of gossip.

It’s an exhausting ritual, but some young Chinese have been testing ways to get around these tireseome duties. Hongbao are meant to be reciprocal—what you give at one wedding, you’re meant to get back at your own. Those not invited can miss out (hence the rationale for keeping constant track).

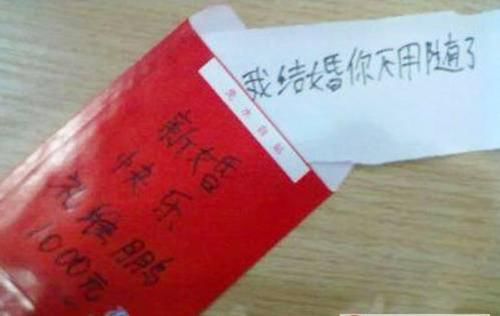

But there’s an obvious way around this: some bolder Chinese have tried giving a note instead, saying that they don’t expect any money at their own wedding, like a reverse IOU.

There’s another, even simpler gambit: an actual IOU. This method is best delivered with a bit of an explanation—you’re totally broke—but that the IOU can be cashed in at your own nuptials.

These gambits, though, are for people who are either short of cash or trying to make a statement, rather than those concerned with social customs and keen to ingratiate themselves with the married couple. Here’s some more diplomatic advice:

FOR THE COUPLE

1. Hold a wedding or, at least, a banquet

A relationship may purely be about two persons in love (or “seeking arrangement”), but marriage involves two families. Regardless of whether the new couple wants a ceremony or not, their families probably do. It’s also an opportunity for them to get back the hongbao they’ve spent on other weddings.

2. Invite the relatives, friends and others you want or need to maintain relationships with

Special occasions signify the close relationship between guests and hosts. Inviting shows the host’s respect and consideration of the guest, and accepting shows respect and consideration on the recipient’s part.

Most Chinese families have one or more “accounting books” that record every hongbao the family has sent out and received. These keep track of the relationships the couple needs to maintain, and could be a guidebook for deciding who to invite. But you should also include other people that you want or need to maintain a close or long-term relationship with, and whose favors you will return.

3. Don’t invite casual acquaintances

The hongbao is presented on the assumption that it will be returned some day. This may not be guaranteed with one’s coworkers, since they may change employment and are separate from your personal life. Therefore, better to not risk inviting a colleague to your wedding unless you have established a good personal relationship.

FOR GUESTS

Guests may fret about how much to include in a hongbao (will you avail yourself of the plus one?). The appropriate sum varies, depending on region, relationship and financial status of both host and guest.

Generally, richer regions like first-tier cities require greater amount. The closer the relationship is, the more money. But not every relative of the bride or groom necessarily has to give a hongbao—since they may be considered part of a bigger family, so their parents’ hongbao will suffice.

1. Consult the family “accounting book”

If there are records of hongbao transaction between the couple’s family and yours, you can refer to the information recorded and give a decent amount back this time by adding 100 RMB or more, depending on the original amount and inflation. If there are no records, consult your parents, who will know all about the “hongbao market” in their hometown. If the couple is from another province or region, play it safe and check how much your mutual friends are giving.

2. Use an auspicious number

Traditionally, some numbers are believed to be auspicious for occasions like weddings. Generally, 2, 6, 8 and 9 are good numbers. For example, instead of 300 RMB, give 299 (二九九, èr jiǔ jiǔ), which is similar to pronunciation of “ai jiu jiu”(爱久久, “love forever”) in Chinese.

Even numbers are preferred to odd ones. For example, 200 RMB is actually better than 300 RMB, while 266 is better than 265. This is not true of all regions, so it’s better to check with locals.

3. Send one guest for each hongbao presented

The cost of wedding banquets is on the rise. At present, it’s reported that one table with 10 seats costs around 1,000 RMB in rural areas, and much more in urban areas. Each seat has a cost. Therefore, it may be best to send only one representative to the banquet for every hongbao that the family presents, even if the whole family wants to send their best wishes in person.

These tips also apply to other social gatherings in China such as funerals, celebrations for a newborn, moving apartments, and being admitted to a prestigious university.

These days, hongbao can be presented in other ways, such as through mobile apps like Alipay and WeChat Wallet, but these simple innovations can prove controversial: one bridesmaid, whose innocent decision to wear an Alipay QR code to a wedding managed to accidentally upset an older relative, sparked more controversy when her picture was published online. Some argued that “money collected through a QR code can’t be a real hongbao because it does not have the hongbao’s inherent meaning and associated happiness.” Others retorted that, although “hongbao were regarded first as a symbol of happiness, secondly for money. Nowadays, it’s the opposite.”

Image courtesy of miui.com