The modern poet who has sent millions of Chinese tourists to Cambridge

Each year, the opening of the Xu Zhimo Poetry and Art Festival at King’s College at the University of Cambridge, leaves UK media scratching their heads over an unexplained trend: Chinese visitors flocking in record numbers to what a sport jacket-clad Cambridge student, interviewed by the BBC in 2013, called the “most boring” bridge on the Cam.

According to Visit Britain, the UK saw 8.3 million Chinese tourists in the first quarter of 2017. Cambridge is one of the most popular destinations, with 14,000 overnight stays between 2014 and 2016.

The UK’s official Visit Britain website cites ancient heritage and contemporary culture as the country’s typical draws for Chinese visitors. However, the bridge (which connects King’s College to a farm plot called Scholar’s Piece) attracts pilgrimages from Chinese tourists who grew up with the work of modern Chinese poet Xu Zhimo (徐志摩), the namesake of the festival—in particular, his poem “Zai Bie Kang Qiao” (《再别康桥》, “On Leaving Cambridge Again”), which is required reading in Chinese middle schools and referenced in songs by Mando-pop artists from Yoga Lin to S.H.E.

Born in 1897 in Zhejiang province, Xu’s career was typical of many Chinese intellectuals who came of age during the education reforms at the turn of the 20th century. Educated in a traditional Confucian academy in his early years, Xu left home at age 14 to study at Hangzhou’s first modern middle school alongside two other future luminaries, writer Yu Dafu (郁达夫) and educator Li Linsi (厉麟似), before embarking on a student career that would take him to Peking University, two years of study in the United States, and finally King’s College in 1920.

In 1923, a year after his return to China, he founded the Crescent Moon literary society, which emphasized lyricism and the preservation of ancient meters and form in reaction to the “free verse” styles championed by the iconoclastic “May Fourth” intellectuals of the time. “Zai Bie Kang Qiao,” which Xu wrote in 1928 after making a return visit to his alma mater, is considered a definitive work of the Crescent Moon movement.

Among his contemporaries, whose writings are often celebrated for their patriotism as well as their literary qualities, Xu’s body of work stands out for its romanticism and pursuit of themes like nature, love, and beauty. His personal life is remembered mostly for its emotional intrigues: He had an affair with architect Lin Huiyin (林徽因) at Cambridge while in an arranged marriage with feminist Zhang Youyi (张幼仪); romanced his second wife, artist Lu Xiaoman (陆小曼), while she was still married to his friend Wang Geng (王赓); and died in a plane crash in 1931, when he was just 34. In his epitaph, Xu’s friend and Crescent Moon cohort Hu Shih (胡适) wrote, “His philosophy in life is one of pure convictions, consisting of just three words: love, freedom, and beauty.”

Xu Zhimo (back row, first from the left) and Lin Huiyin (front row, first from the left) accompanied Hindu poet Rabindranath Tagore during his visit to China in 1924 (VCG)

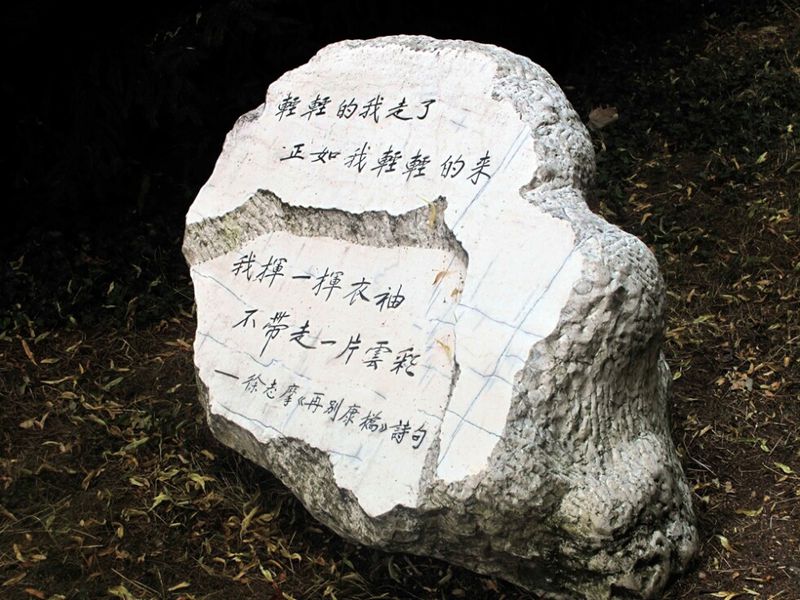

The poem is taught in Chinese schools as an example of Western influences on modern Chinese poetry. Chinese scholars like to compare both Xu’s life and work with those of English romantic poets such as Percy Shelley and John Keats—and perhaps it’s the poem’s “English” atmospherics, and the sumptuous descriptions of natural beauty along the river, that send Chinese literary pilgrims to King’s College. The college has been doing what it can to attract them: In 2008, a stone carved with the first and last lines of Xu’s poem was placed beside the bridge. Xu’s namesake festival was started in 2015, with a theme each year that celebrate some aspect of British-Chinese cultural connections, such as gardening and landscaping.

For those who want to make this pilgrimage by proxy, here’s a translation of the poem, taken from the book The University of Cambridge: An 800th Anniversary Portrait:

On Leaving Cambridge Again

轻轻的我走了,

正如我轻轻的来;

我轻轻的招手,

作别西天的云彩。

Softly I am leaving,

Just as softly as I came;

I softly wave goodbye

To the clouds in the western sky.

那河畔的金柳,

是夕阳中的新娘;

波光里的艳影,

在我的心头荡漾。

The golden willows by the riverside

Are young brides in the setting sun;

Their glittering reflections on the shimmering river

Keep undulating in my heart.

软泥上的青荇,

油油的在水底招摇;

在康河的柔波里,

我甘心做一条水草!

The green tape grass rooted in the soft mud

Sways leisurely in the water;

I am willing to be such a waterweed

In the gentle flow of the River Cam.

那榆荫下的一潭,

不是清泉,

是天上虹;

揉碎在浮藻间,

沉淀着彩虹似的梦。

That pool in the shade of elm trees

Holds not clear spring water, but a rainbow

Crumpled in the midst of duckweeds,

Where rainbow-like dreams settle.

寻梦?撑一支长篙,

向青草更青处漫溯;

满载一船星辉,

在星辉斑斓里放歌。

To seek a dream? Go punting with a long pole,

Upstream to where green grass is greener,

With the punt laden with starlight,

And sing out loud in its radiance.

但我不能放歌,

悄悄是别离的笙箫;

夏虫也为我沉默,

沉默是今晚的康桥!

Yet now I cannot sing out loud,

Peace is my farewell music;

Even crickets are now silent for me,

For Cambridge this evening is silent.

悄悄的我走了,

正如我悄悄的来;

我挥一挥衣袖,

不带走一片云彩。

Quietly I am leaving,

Just as quietly as I came;

Gently waving my sleeve,

I am not taking away a single cloud.

All images from VCG