Shanghai “socialites” accused of fraud exposes industry behind faking wealth for social media and marriage

Chinese social media is awash with young socialites flaunting their wealth and luxurious lifestyle with photos of global travel, expensive hotel rooms, luxury bags, and cars. But these mingyuan (名媛, “socialites”) now stand accused of faking their wealth, with a very different reality lurking behind the staged photos.

An article published by WeChat account Lizhonger on October 12 exposed these supposedly wealthy individuals as mere wannabes, staging photo shoots and pooling resources to give the appearance of wealth and status. The article received over 1.4 billion views and 120,000 comments in two days.

According to the author, he paid a 500 RMB admission fee to join a WeChat group for Shanghai mingyuan. The group, with the tagline “Youth, Fashion, Money,” claims to allow members to exchange luxury goods, have afternoon tea together, hang out with internet celebrities, and meet with financial tycoons.

Screenshots provided by the author, though, show that members are in fact clubbing together to “group buy” luxury items and services—six people to buy a two-person afternoon tea set worth 500 RMB at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, 15 to share the cost of a 3,000 RMB hotel room—not in order to consume them, but simply to take photos for social media. Members even promise to leave the food untouched and the hotel bathrobe pristine so that others could get the best shots.

Screenshots provided by Lizhonger showing members “crowdfunding” for a room at the Ritz and discussing how to take photos

The idea of mingyuan originates from the ancient concept of high-born young ladies, or mingmen guixiu (名门闺秀). The term, though, emerged in the 1920s and 1930s and was typically associated with Shanghai’s high society. It generally referred to pretty ladies of noble birth or from a wealthy background, who often play a prominent role in the nation or are frequently involved in fashionable social gatherings.

In response to Lizhonger’s exposé, a member of the Shanghai WeChat group who identified herself as Feifei told Xinmin Weekly that the group allowed women like her, who earn a salary of around 5,000 RMB per month, to have a taste of wealthy life. “I don’t think there is anything wrong with spending our own money on things we desire,” she argued.

These arguments have been met with little sympathy, however, as many censure what they perceive as the women’s dishonesty and “worship of wealth,” as well as their attempts to use their fake socialite persona to pick up rich men. Screenshots by Lizhonger show one member discussing how she refused one Rolex-wearing man’s date request because he drove a BMW, rather than a Ferrari, and declined to go shopping with her. “The poor BMW owners are often cheap,” several members agreed.

The traditional concept of “matching backgrounds” (门当户对), which dates back at least to the Yuan dynasty (1206 – 1368) and emphasizes marriages based on matching social and family status, provides a powerful incentive for women to improve their social status (or at least appear to occupy a higher position on the social ladder). Though some critizes the notion as a feudal, similiarities in life experiences and values continue to be emphasized in modern Chinese matchmaking.

In today’s market economy, consumer goods have become common symbols of social status, leading upwardly mobile youngsters to believe that they can “match” a wealthier partner’s background simply by spending. Flight attendant Xuan Yun and model Fang Yuan, who are married to Hong Kong entertainers Wilber Pan and Aaron Kwok, are cited as successful examples such modern Cinderellas.

After Xuan and Pan’s marriage in July, Wang Sicong, son of Wang Jianlin, one of China’s richest men, alleged that both women had been trained to be “wives of kings” by a woman named Amy, who denied the rumor. Many netizens, however, continue to believe Wang, citing several photos on social media that show the two women in the same posture, with the same handbags and in the same settings.

The practice of faking high-end consumption is not new, and was originally associated with men entrolled in “pickup artist (PUA)” courses that were introduced to China in the 2010s. These courses aim to make trainees more desirable to women by recreating their profiles and making them appear rich and successful.

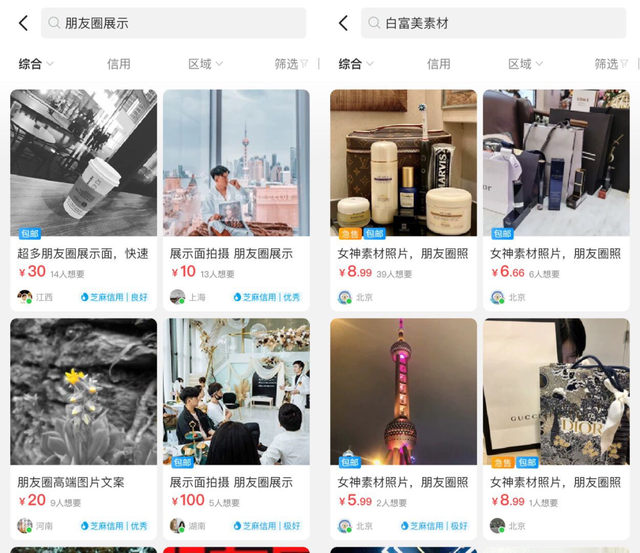

On online shopping platforms like Taobao and Xianyu, consumers can purchase ready-made photos to display on their social media profiles. Advertised under keywords such as “Pale, rich, and beautiful material,” and “Goddess material (女神素材),” one can find photos of luxury cars, handbags, hotel rooms, and other fancy settings for between 5.99 and 100 RMB. One can also pay 98 RMB for software to change the location of photos in one’s WeChat Moments in order to pose as a world traveler.

Screenshots from Xianyu purporting to show photographs one could purchase for one’s social media accounts

To appear in the photographs themselves, wannabe socialites can hire companies to help get the perfect shot. Shusheng CLUB, a WeChat business which specializes in this field, charges around 2,000 to 5,000 RMB per person for a two-day photo shoot in Shanghai featuring around 10 scenes, such as a luxury hotel suite with the Oriental Pearl Tower and the Bund in the background.

In her WeChat account, writer Hou Hongbin pointed out that the fake mingyuan scandal is a representation of “money-worship” among young women. She attributes the temptation to “fake it” to social pressures that “tell [women] ‘girls should enjoy life as early as possible, and buy name brands…men are only attracted to those of the same social status as themselves, and you need to package yourself properly in order to match rich men.’”

On the other hand, a woman interviewed by People magazine, whom the author claims to be a “real” socialite, stated that China’s elite circles are exclusive, that wealthy men are unlikely to fall for the “fake” mingyuan’s deception, and their social gatherings involve many subtle rules of etiquette and values that the nouveau riche are unlikely to grasp.

Such views appear to be confirmed by July’s hit TV series Nothing But Thirty, whose protagonist Gu Jia, owner of a firework factory, is excluded from a community of wealthier wives, despite her efforts to fit in by swapping her Chanel handbag to a limited edition Hermes. Even Chinese actress Yang Ying, or Angelbaby, whose extravagant 210 million RMB wedding made international news in 2015, was recently ridiculed for photographs showing her standing on the sidelines among a group of lesser-known women with wealthy backgrounds.

This raises the question of who the WeChat mingyuan are trying to attract, and whether they would really like life among the elite. Perhaps, instead, the pickup artist who pretends to be rich and the wannabe mingyuan might be a match made in heaven.

Cover image from VCG