How to express love to a person who cannot hear?

This story is published as part of TWOC’s new collaboration with Story FM, a renowned storytelling podcast in China. It has been translated from Chinese by TWOC and edited for clarity. The original can be listened to on Story FM’s channel on Himalaya and Apple Podcasts (in Chinese only).

1

I’ve always known that my mother could neither speak nor hear

I must have been aware of the fact that my mother is deaf since I was little. Children demand attention from adults from a very early age—for instance, by crying so that adults will comfort them. But at that age, I rarely got a prompt response from my mother.

When I was very young, and it was very cold in winter, my mother put me on the kitchen range where a pot of water was boiling over the fire. I think I wanted to warm myself up, so I stuck my hand right in the boiling water. I wailed in pain, but my mother couldn’t hear me. I must have cried for a long time before I was found, and my hand was badly burned.

My mother was new to motherhood when she had me. Adding in her deafness, I would say I had to deal with a lot as a kid. But I don’t think it was all that bad. After all, things were tough for her as well. She was anxious much of the time, not knowing what to do. She started getting white hairs at 37 or 38, worrying about so many things in life. She worried about how I ate, how sickly I was—how small and weak—and about our family’s difficult circumstances.

It was only later, when I was older, that I noticed another characteristic about her: She couldn’t cry. Maybe there was a biological reason, but she produced no tears, and she didn’t sweat. She would cry out when she was in pain, but she never shed any tears.

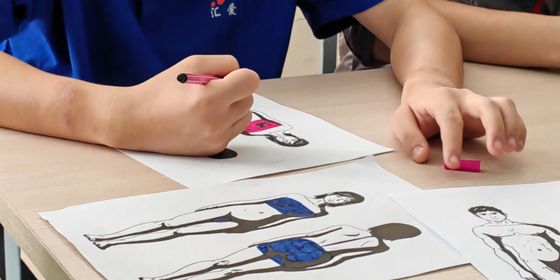

Movie still from 2007 drama My Ugly Mother

2

A special sign language

Because of my mother’s deafness, I felt inferior when I was little. I remember that when I first started going to school, my mother would come with me. But I didn’t want my classmates to find out that my mother was deaf, so I didn’t want her to go with me anymore. One day after getting home, I pointed at my mother, then pointed toward the school, and made a gesture for “no.” She stared at me blankly for a moment, then nodded to show that she understood. After that, she didn’t walk me to school anymore, but she would stand on the outskirts of the village to watch the road as I returned.

Interacting with my mother was actually quite easy when I was a child. For example, if I wanted to talk about a classmate, I’d pretend to put on a shoulder bag and perform a Young Pioneers salute, and she would know I was referring to my classmate. If I pretended to put on glasses and pull at my hair, she would know it was the teacher. I think this all came about naturally, as we had few other ways of communicating. So from the start, I used actions to express myself.

My mother is actually a very smart person. She’s great at making chili bean paste. She can turn old clothes into mops and rope. She even knows how to haggle when she’s shopping, by gesturing with her fingers.

3

No stranger to solitude

When I was 4 or 5, my birth father died in an accident. My mother remarried, and we moved to my stepfather’s village. I was pretty happy before my mother remarried, since I had lots of uncles, and their kids looked out for me.

After my mother remarried, we moved to my stepfather’s village. The kids there found my mother an oddity, and would occasionally come to the door to gawk at her. Sometimes they would call her dumb to her face.

When I was 5 or 6, I tried to find other kids to play with in the village, but they bullied me because my mother was different. One time they tricked me, saying they would give me a “red ring.” They rubbed a blister into the middle finger of my left hand, and rubbed it until it bled. When the blood congealed, they drew on the rest of the band, making it look like a ruby ring. I was too stunned to react. I only knew the pain.

I must have gotten into my solitary habits at a young age. In order to find happiness, I had to make it myself.

When I was little, the adults in the village would take a nap after lunch. But kids have boundless energy, so we would all come out and play. The other kids would gather to play marbles or something, but I preferred to stay at home or watch ants under a tree, rather than playing with them.

Later, in middle school, there were some other memorable events. One time, I tore a friend’s clothes while playing basketball with him. I knew I was at fault, and that classmate was definitely going to beat me up. But I didn’t want to make any trouble at school—my father never had time, and I didn’t want my mother to show up in front of everyone. So in that moment I decided to just let him hit me. As long as I didn’t fight back, and he threw the first punch, I would be in the clear. This way I wouldn’t have to take blame for my mistake, and my parents wouldn’t be called to the school.

Later, that classmate did come for me. He pinned me against the wall by my neck, and I didn’t resist. Then it was over, and neither of us bothered the other again.

When I was 6 or 7, my mother and stepfather had my little brother.

I remember the day he was born. I was playing in the village when an auntie rushed over and told me that my mother had given birth. I was dazed—I think my first thought was to go and hide in a corner. I didn’t want any of this to be happening.

I remember in elementary school, it was easy to win awards at school. When I took the certificates home, my father would be out, and my mother didn’t know what they were. She couldn’t read, so I think she just stuffed them into some nook of the house.

Later, when my little brother started school, he also won awards. By then my mother knew they were some sort of honor, and would ask me, where are your awards? I felt so hurt and angry at the time, because I thought my own awards hadn’t been acknowledged. My certificates had been burned up as kindling for the cooking fire. By the time I wanted to claim some credit, it had already burned to ash.

In middle school, we went home once a week, and our parents would give us some money for food. I would often put some aside to buy snacks or toys that I liked. But it was almost like clockwork: whenever I saved money, I would get sick.

I never considered that I was getting sick from saving money and not eating. Instead, I felt it was because when my mother and I were separated for too long, I felt invisible.

At home, I still got some love. Although my mother couldn’t talk, she would watch my every movement. She would watch me eating and drinking, running and jumping; then I felt seen.

4

Choosing my own future

At home, my father didn’t like to talk, and my mother couldn’t talk. So we didn’t have much conversation in our family, and it was hard to express any complex ideas.

After graduating from junior high, I decided to go to vocational school. It was a kind of school where you had to work hard, but didn’t need to talk much, so I thought it would be a good fit for me. I didn’t discuss my plans with anyone else. I just went home and asked my mother for the school fees, and went to register.

When I was attending vocational school, companies would come to recruit us. They would ask if the students wanted to work for them. Almost all of the other students said they had to talk it over with their families, but I agreed to go on the spot. I wasn’t going to discuss things with my family. It seemed providential. The company bosses rejected everyone who needed to talk things over, and took only me. At the age of 20, I went alone to Shanghai to work, carrying a big bag.

5

My mother’s self-worth

My father worked in the coal mine, but when he got older, the mine didn’t want him anymore. He couldn’t find any other work that suited him, so he just lay around at home. He might have been somewhat depressed—he didn’t do farm work, nor did he go out to talk to anyone. At home, he relied on my mother to feed and clothe him.

My mother appeared to love and hate him at the same time: love, because she demonstrated her worth by taking care of others; hate, because she didn’t like to see my father lying around all day, and hoped that he could get out more. Later on, when my mother went out to do farm work, she would drag him along as well.

One year during the Spring Festival, I felt that I had been away from home for too many years, and my mother was working too hard. I wanted to do something for my family, so I decided to cook the Spring Festival Eve dinner myself. But when I finished cooking, and everything was ready for us to eat, I noticed that my mother actually wasn’t happy.

She had discovered that her child was grown, and didn’t need her anymore. That expression on my mother’s face, like she had lost her worth—it might have been disappointment. After that, I never cooked at home again. I felt that if she already couldn’t talk, it would be adding another layer of harm to take away this piece of my mother’s self-worth.

6

I got used to staying silent

I think my mother’s biggest influence was on my ability to express myself. I remember that when I was working in Shanghai, the company encouraged us to tell one of our colleagues after we finished a task, “I just did this.” But I felt subconsciously that even if I said this, I wouldn’t be heard. That was what it was like at home, with my father always out and my mother unable to hear. Nobody ever answered me, so I stopped expressing myself long ago.

When it comes to expressing affection for others, I also take after my mother. I’m silently there for you, observing every movement. I listen for what you need, and quietly go and do it or buy it. I have had a few relationships when I knew we liked each other, but since I only express love by being there for them silently, those feelings came to nothing.

Movie still from 2007 drama My Ugly Mother

7

Our interactions today

Because my mother has been deaf since childhood, and she never learned to read, it was very difficult to stay in touch when I left home. But now that we have smartphones, we communicate much more easily and frequently.

Whenever I return home after another year away, the front gate would be open, and I could see my mother sitting and working in the courtyard. I would walk up behind her and pat her on the back. That’s how she knew I was back. She’s always excited to see me, and tells me how worried she has been. Then I explain that I have been very far away. I point into the distance and raise my finger higher and higher, pointing farther and farther away. Then she understands.

Later on, after I bought her a smart phone, we started having video calls. I do my work, and she prepares a meal. She watches me, and I watch her. Sometimes we send emojis to each other—hugs, roses, smiley faces; she understands all of these.

Hoping to relieve her boredom, I taught her how to use Douyin and Kuaishou. Though she isn’t able to hear, she can see what people are doing, and can use the apps that way.

When my mother thinks of me, she sends me an emoji, and I send one back. That’s how she confirms I’m alive. Sometimes, if I don’t respond, she has my father call me to make sure I’m still okay.

Crops, fruits, and flowers in Xiao Wu’s hometown

I’ve already lived away from home for ten years now. I’ve lived in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Now that I’m almost 30, I want to return to my parents’ side. I especially want to spend more time with my mother. I hope that our lonely hearts can make some company for each other.

When I was little, my favorite thing to do was to lie in my mother’s lap. I would bask in the sun, with light filtering through the ends of her hair onto my face. She would take an earpick and scoop the wax from my ears. That made me feel so safe, so at ease.

Translated by J.Y. Gan

Cover image from VCG